|

Understanding Money |

In this section we break down a number of points into bite-sized pieces. You can find them recreated on a single page here.

1. How Money Really Works

An Example

In order to show how money really works, we can offer a simple example. We'll build a small financial system that shows how communities create and use money, and how things like banks and debts really work too.

We'll keep it very simple. We'll start with a very small community, a community of just 5 people, who have skills they want to trade among themselves, in what we could call a 'local economy'. We'll show how they can interact with each other using money and doing so will capture how we interact with each other in much larger societies, indeed the world as a whole, today.

A Basic Financial System

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | 0 | 0 |

| Jo | 0 | 0 |

| Cassie | 0 | 0 |

| Lauren | 0 | 0 |

| Sean | 0 | 0 |

- Table 1 -

The above table shows the community members' finances at the beginning. The fact that the table is filled with zeros means there's no money in this community yet. But that's not a problem, because Mark, Jo, Cassie, Lauren and Sean all read the moneytruth.org website and they know perfectly well how to get the system up and running.

The reason we have money, of course, is to have a common medium for exchange - something to offer others in return for doing things for us. Using money we can pay people to build things, grow things, repair things, move things around etc. and we can be paid for the things we do for other people too. By being universally accepted, money overcomes a number of difficulties that would otherwise exist in organizing exchange. And money also provides a means by which to make savings, allowing us to control our balance of giving and receiving over time.

Now let's imagine that Sean will need some money because he needs emergency repairs to be carried out on his roof. Although no money exists right now, Sean knows that he can hire and pay Mark - a skilled roofer - to do the job. And he knows that he can hire him and pay him right now, right when the work needs to be done, even though he doesn't currently appear to have the money to do so.

In this system, what we do when people need money is simply create it. Sean will need 1000 units of currency to pay Mark for his work and we can create that money right now. All that needs to happen to allow us to do that is for Sean to legally agree that he has a debt for the same amount and that he must therefore pay it back. So long as Sean agrees, we can create the money which will pay Mark and will go on to circulate in the economy:

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Sean | ▴1000 | ▾1000 |

- Table 2 -

In the above table, we can see money being created for Sean. You can see that it is created as a simultaneous record of credits and a debt of the exact same size. And now that money exists it can be transferred in a payment from Sean to Mark:

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | ▴1000 | 0 |

| Jo | 0 | 0 |

| Cassie | 0 | 0 |

| Lauren | 0 | 0 |

| Sean | 0 | ▾1000 |

- Table 3 -

What you saw above really was the creation of money. Sean's debt really did create 1000 currency units on the system - and we didn't need a King or a Queen, a stately government ruler, or fancy printing or coin-stamping machines. The money was created as a transferable numerical record; a simple number in a ledger and nothing else.

Now, some readers may feel this is just too simplistic to describe the reality of money creation in the modern economy. But this is in fact exactly how money is created; not only by financial institutions in our own economy, but by financial institutions all over the world. And it really isn't modern either; financing has worked this way for as far back into history as you care to look.

Indeed, it stands to reason that money creation and financing should be as simple as this. Every firm and every activity humans undertake we try to make as streamlined, as efficient, as we possibly can. And this is how we do that in the financial world. Any other concept of financing, or any other way to go about these processes, of creating money and/or facilitating debts, would simply be more cumbersome, more inconvenient and more expensive. Creating money 'on demand', when people need it, is simply the most efficient way to go about 'doing' money and finance.

Feel free to pause at this point if you need to.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

So... we've seen money being created. Sean has a legally binding debt on the system and Mark, having provided the materials and labor to repair Sean's roof, quite rightly is the possessor of (he is the 'bearer' of) the corresponding number of legal claims. Mark can now spend that money on whatever he likes. Or, alternatively, he can save it.

But, we also saw something very much of equal importance: We saw debts being facilitated without the need to lend or borrow money. And that means the justification for charging or taking interest on these debts has been removed.

Recap that:

Sean didn't have to leave his roof in a state of disrepair while he labored elsewhere for a wage, 'saving up' the money to pay Mark.

-

He also didn't have to seek out someone who could lend him money, thus he did not have to enter a lender-borrow relationship or pay interest.

And that leads us to one of the most important observations we can make in the field of monetary economics: Everyone can have access to money free of unwarranted lender-borrower relations and free of interest. (Banks, of course, can take competitive fees for the services they provide, but access to money should be available to all interest free, 0% + fees.)

Let's continue with another example. Lauren would like to extend her property. Lauren's property is also the location of her daycare business, so extending it will allow her to expand her business and her ability to serve the community. Just as above, Lauren can enter into a legally binding 'promise to pay' in order to create the money that will pay for the work to be done. She will take on a debt, 2000 units this time, and Jo - a skilled builder - will carry out the work that will earn him the title to those claims.

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | 1000 | 0 |

| Jo | ▴2000 | 0 |

| Cassie | 0 | 0 |

| Lauren | 0 | ▾2000 |

| Sean | 0 | 1000 |

- Table 4 -

Once again, we can see that money has been created and then transferred in payment. And again we can see the two-sided, relational nature of money. Jo has labored for Lauren's benefit and he is now 2000 currency units better off. Lauren has extended her property and her business, but she is now 2000 currency units in debt.

Notice that Mark and Jo now have money that they can spend. And that means if they don't want to spend more than they already have, they won't need to create any more money. Indeed, the economy as a whole won't need to create more money until someone needs to go into debt. The money that already exists in the economy will continue to circulate until it has been settled again. That is, until the debt which created it is paid down.

We can show that happening now. The following table shows a transaction between Mark and Lauren. Mark (the roof repairer) has a young child who he would like to enroll in daycare with Lauren. The charge, for the remainder of the period, will be 1000.

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | ▾0 | 0 |

| Jo | 2000 | 0 |

| Cassie | 0 | 0 |

| Lauren | ▴1000 | 2000 |

| Sean | 0 | 1000 |

- Table 5 -

By comparing Tables 4 and 5 you can see that Mark's account is debited by 1000 and Lauren's account is credited by 1000. Mark goes from +1000 credits to 0 and Lauren's account shows that, while she has a debt of 2000, her credits go from 0 to 1000. Notice that there are still 3000 units of currency in existence (the total in each column), but Lauren now has credits which she can use to pay down her debts, if she would like to.

Let's see now how Lauren can pay 1000 units from her credits column into her debt column to pay off part of her debt. Notice that when she does so, that money is paid out of existence again.

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | 0 | 0 |

| Jo | 2000 | 0 |

| Cassie | 0 | 0 |

| Lauren | ▾0 | ▴1000 |

| Sean | 0 | 1000 |

- Table 6 -

By transferring 1000 currency units from her credit column to her debt column, Lauren paid off part of her debt. And in doing so, she actually removed those 1000 units of currency from the system. The money creation we saw earlier has just been reversed - money has been uncreated again. There are now only 2000 currency units remaining in circulation.

What we've seen - the creation, transfer and settlement of money - can be called the 'lifecycle' of money. And it is now very easy to imagine almost any transaction we like between members of the community. We can imagine anyone going into debt and creating more money, we can imagine anyone paying money to anyone or even everyone else, and we can imagine anyone paying down debts to eliminate money that their own debts created. We can even imagine everyone paying off all their debts, returning us to where we began at the beginning, with nothing but zeros in our system and thus no money and no debts at all.

While there's more we can (and will) go on to talk about, having seen money being created, having seen it being transferred in payments and eventually settled again, we've seen surely the most important things we can know about money and monetary economies:

-

We've seen that money is created 'on demand', as we need it, when we go into debt. And because of that, we can say this money somehow represents that debt, or is a special form of debt.

-

We've seen that debt is facilitated, not by the "lending" or "borrowing" of anyone else's money, but by creating new money, endogenously, within the system.

-

We've seen that money is not returned to a prior owner when it is repaid, but is in fact paid out of existence again.

These realities may at first seem jarring, for those used to thinking about money in physical terms i.e. physcial objects like banknotes or coins. Obviously, physical monies don't just disappear when you pay them back. But remember, so far, we haven't yet introduced any physical money into our system. Everything we did was done with accounts entries and nothing more; simple, legally enforceable numerical records. And, in later discussions (4. Physical Money) you'll see that when we do introduce physical money like banknotes and coins, it really doesn't change what is happening underneath. Physical money really just 'adds on' to our money system, in very small quantities, enabling hand-to-hand trades and the transfer of accounts information (numbers) outside of the banks' secure communications networks.

We won't go into any greater detail on the following point here, but it is for the very same reasons outlined above that governments too should have interest-free access to money/credit on the international stage. Just as domestic banks serve households, international banks serve nation states. And they can and should facilitate international debts and trades in the very same way. We could summarize that by saying: All entities protected by democratic or human rights should have access to money/credit free of unnecessary lender-borrower relations and free of interest.

Money, banks and debts work very differently to the way we commonly believe. And you've seen that the system we have offers very clever solutions to many of the greatest social and economic problems that exist - many of the greatest historical problems associated with money, debt and the relationship between the rich and the poor.

We'll go on to add more to this model in upcoming sections, including adding a government and a plurality of banks in Sections 8 and 9.

2. Conceptualizing Money

The Fountain of Money at the Heart of All Economics

This one is just a little conceptual aid, for those who might benefit from it. I think it can help to make sense of economic reality and aid in breaking down some unhelpful economic myths.

This one is just a little conceptual aid, for those who might benefit from it. I think it can help to make sense of economic reality and aid in breaking down some unhelpful economic myths.

I'm sure you've heard people say "Money doesn't grow on trees!" "There's no such thing as a magic money tree!" etc. But the fact is that all money has to be created and we create it through processes which make money creation as simple and inexpensive as possible. You could think of these processes as magic money trees, but I prefer to think of them as fountains of money that exist at the heart of all our economies. And they've really always been there.

If you've read a little on this website already, you'll know that money really does just come into being when people (or in fact governments) need it, when they ask for it and go through the proper processes to create it. In other words, without much effort or fuss, money really does just come into being, when it is called upon, as if from a magical source like a fountain or a tree.

I prefer the analogy of the fountain because money is a resource that, for most of us, must be returned if we go with our hands open (or a bucket) and ask for some. We 'take on a debt' - and we know that when we do that, those debts should be repaid. As you'll see, governments, in some circumstances, should be exceptions to that rule, but for everyone else, for ordinary people like you and me, money comes into being when we need it, on the condition - the legal condition - that we commit to paying it back.

Money - and thus our theoretical magic fountain - is effectively infinite. There's no real upper limit to the amount of money that could be created. And that of course presents us with a problem. If money creation were allowed to go on unrestrained, it would soon become extremely unstable. Money, then, must be carefully controlled. And insisting that most money created is returned (uncreated) again is a fundamental part of how we control it.

We can be reasonably sure that money will always be like this. Money is not and surely cannot be some kind of physical 'thing', something inconvenient and expensive to ship about the planet each and every time a transaction is made - only to be shipped straight back again when the next transaction is made in the other direction. Money inevitably resolves to weightless, easily transferable numbers (mere accounting) that can be sent and received all over the world with the minimum of fuss and expense. That's just an inevitable practical reality for money, as was assuredly discovered by those working, millennia ago, at the very beginning of the story of money and finance.

3. Public Money Creation

Breaking it Down

We've said that two of the most elementary observations that can be made in the field of monetary economics are:

- Every country should have a debt-and-interest-free national currency base.

- All households and all governments should have access to interest free financing.

And that's because money is created in two spheres:

- The public sector.

- The private sector.

Both of which should be democratically legitimate at their foundation.

In our first bite-sized piece, we looked at the basic foundation of money and saw why all households (and all governments) should have access to money/credit interest-free (0% + fees). Let's now look at the creation or facilitation of a democratic, reliable national base currency.

It would be pretty straightforward to simply state that every country should have a democratic, debt-and-interest-free national currency base and leave it there. Who would disagree? Most people, if they were to analyze their thinking, would assume that something like that is already the case, that governments create money democratically... because that's what they're there for.

And the idea that governments should have to 'borrow' a national currency base, into existence, as a debt repayable with interest, is illegitimate on its face.

But it's worth exploring more and seeking greater clarification around the nature of these processes and the relationships they engender. Furthermore, we might still ask: If money is inherently debt-based, then would a publicly-issued currency base still be a public debt? If so, to whom?

When we looked at private sector money creation for households, we saw something that should be democratically legitimate but in practice wasn't. Households' access to money (to money creation) is presented to households as 'loans' of already existing money. This allows the financial sector to achieve steep supernormal profits by taking interest, as "compensation" for those "putting up" and "foregoing use of" their money. Well, the same structural relationship exists for national governments too. National governments, just like households, 'borrow' money into existence from banks (albeit central banks in this case). Thus they enter into 'lender-borrower' relationships in which monies are recorded as debts to be repaid, along with interest as compensation for lenders for the foregone use of loaned money. Just as it was for households, this process constitutes the public sector's contribution to the money supply.

So, despite the apparent impropriety of this arrangment, one thing we can say is that it is at least consistent: Money is created for both the private and public sectors the same way: Through bank 'loans'.

In some ways this shouldn't surprise us. We saw how banks create the private sector's contribution to the money supply. And we've seen that money is, fundamentally, transferable records of debt which are given their life within the banking system. Thus we've seen that money is, for the most part at least, "a creature of the banking system" - something that contrasts well with the popular belief that money is a "creature of the state". So the idea that public money creation might also be taking place through banks is perhaps not entirely surprising.

But we should be surprised that governments too, like households, must 'borrow' money into existence as 'loans' repayable with interest. These debts are expensive and they weigh heavily on national finances all over the world, resulting in the run-down of public services ('austerity') and the transfer of money and assets from unfairly indebted public sectors to those taken to be "lenders" to the state.

We saw that, in the private sector, money can and should be created much more democratically - interest free. So we would expect to see something at least that democratic as that in the public sector. If money created for households should be "a debt but interest-free", would we expect a national currency base to be a debt but interest-free too?

Well, let's begin by reasserting the most important point of all: If democratic public money creation can be described as a debt, then it must be a very different kind of debt to that which we have today: debts associated with 'lending' and 'borrowing' and owed by society to those taken to be lenders to the state. If, then, public money creation can be described as a debt, it must be a debt owed by society either to the holders of that currency, or to society itself.

Unsurprisingly, this is simply one of those areas where the public sector is a special case. And we can arrive at the same conclusion no matter what concept we have of money (e.g. chartalist, or debt-based...) so long as we believe money can be issued democratically by or for national public sectors.

Public sector money creation, just like private sector money creation, adds to the overall amount of currency in circulation - which we could envisage as a big pool in the heart of our economies. When money is created, the pool grows; when money is repaid, the pool shrinks. All other things being equal, if money is created and paid back in balance, the pool would remain consistent in its size.

We instinctively feel that when money is created for ordinary people, like you and me, we must honor it - that is, we must pay it down again. But not, of course, because it was "someone else's money". The money was created when we needed it and never belonged to anyone prior to that. The reason we must pay this money back comes down to a general sense of fairness and the fact that if everyone could go into debt (which creates money) and not honor it, then we'd all drown in a pool of money growing bigger and bigger without any reciprocal effort to pay it away again.

We pay money back to the financial system, not because it was "someone else's money", but to maintan:

-

Fairness

-

Stability

in the system.

Public sector financing, like private sector financing, would expand money through issuance and shrink money through receipts; be they taxes, or non-tax revenues like sales of public goods and services.

But... should we think of money issued/created that way as a debt, in the same way we understand it is a debt for households?

Well, as stated, it must be a debt either to the holders of currency (because they are holders of these articles of so-called government debt), or to society as a whole (because that's who issued and gave primary legitimacy to the currency in the first place) - groups which may in fact be largely indistinguishable. If we take it to be a debt we owe to society, then it is a debt society owes to society, "a debt we owe ourselves"... which surely cannot be described as a debt at all. What does it mean to say that you owe yourself $100, or an ounce of gold? If we take it to be a debt to the holders of currency, then what would we owe them? We would owe them the acknowledgement and respect of their legal titles and their ability to redeem those titles on the system; we owe it to the holders of money to accept their money in payment for goods and services - and note, that's across all of society, not just 'taxes'. But this latter kind of debt is in fact not what we saw with households.

In the case of household debt, we saw it was a very active obligation. Households are obligated to go out and recover the money their debts created in order to pay it away again. And that was to maintain the fairness and stability of the system. It would be no good at all if such debts were passive: a debtor could simply indebt himself for a large sum and then spend that money lying in luxury on a tropical beach. He could claim to be "willing to accept common currency in return for his efforts", but then choose to spend the rest of his days making no effort at all. Clearly, no system could work like that.

So we've reached a logical dead-end and unless someone has a very good reason to make a government do what households have to do (i.e. pay out of existence all the units of currency they create), then these cannot be equivalent obligations or debts. Indeed, governments appear to have a very much contrary obligation: to provide a persistent currency base that allows people to make savings, immune from banks' demands for repayment. That wouldn't be possible if every unit of currency in circulation were a debt that someone insisted had to be paid away again.

In the case of households, we saw that they did indeed have an obligation "to recover all the units of currency they create and pay them away again." But in the case of nation states, there is no such corresponding obligation. The most we can say, I think, is that they have an obligation to do all that is possible to maintain the system in its stability and fairness. These are two very different obligations for two very different entities: individuals vs the speical case of all of us together as a whole.

I think we can state, with confidence, that the closest we can get to the idea that publicly created money might be a debt is to say that it is a "debt we owe oursevles", therefore in reality not a debt at all. We've seen that governments have clear obligations when it comes to money, but this is very different to believing or announcing that this money is still somehow a debt.

And that is true whether you accept money is debt-based (you should) or choose to believe it is or should be chartalist. While society clearly benefits from knowing how much money a public sector has contributed to a currency's overall supply, there is just no reason to record that issuance as a debt.

And we shouldn't let an overzealous attachment to banks' balance sheet accounting conventions lead us astray either. There's no reason for public central banks to record this money as 'liabilities' and there's no reason to 'balance them off' against interest bearing government assets either. Even if we accept the terms 'assets' and 'liabilities' to describe the creation and circulation of money, the public sector is an obvious special case and we shouldn't expect the government's bank to account for itself the way a private commercial bank does.

Let's tie this up with an outline of 4 different types of debt that we see again and again:

-

Debt arising from household's access to financial services: This is a real debt. It might not be the result of 'lending' or 'borrowing', so should not have interest added to it (0% + fees), but it is a debt and should be honored.

-

Debt arising from the lending and borrowing of already-existing money: This category of debt would be a real debt and interest is sure to be payable. It is, however, in most cases, the most socially destructive form of debt. Few people who have access to banking services in a democratic society should be left to face this kind of option. Both democratic and human rights should offer a high level of protection first, by ensuring universal access to interest-free financing.

-

National debts derived from the creation of a national currency base by central banks: This category of debt is really not a debt at all. Public money creation is a basic democratic necessity; a necessary public good and public right.

-

The international debts of nation states: These are the governmental equivalent of household debts. Just like household debts, these are facilitated by banks creating money endogenously. They are real debts, but they too should be interest-free.

4. Physical Money

Nothing More Than a Communications Device

Physical notes and coins exist in the smallest number possible to facilitate day to day trades, to convey accounts information outside the banks' secure networks. In other words, they are simply durable, reasonably secure communications devices, carrying accounts information, hand-to-hand, across the economy. The materials of which modern money is made have no intrinsic value, you could not get anything for the paper or base metals out of which they are made. But neither are they supposed to, because they only exist to carry information. You could liken money to any other legal agreement that might be recorded on paper; the paper on which a contract is signed has no intrinsic value, its value lies in the information or agreement it memorializes.

Physical notes and coins exist in the smallest number possible to facilitate day to day trades, to convey accounts information outside the banks' secure networks. In other words, they are simply durable, reasonably secure communications devices, carrying accounts information, hand-to-hand, across the economy. The materials of which modern money is made have no intrinsic value, you could not get anything for the paper or base metals out of which they are made. But neither are they supposed to, because they only exist to carry information. You could liken money to any other legal agreement that might be recorded on paper; the paper on which a contract is signed has no intrinsic value, its value lies in the information or agreement it memorializes.

Creating this kind of physical money, we would think, should be the responsibility of an accountable authority. The reason being that physical money represents the legal claim a bearer has on society, not its commensurate debt. Creating physical money free of its commensurate debt is, of course, the essence of counterfeiting (unless it is done democratically - see here). Equally, when precious metals figured to an extent within the physical money supply, accountable figures would have been expected to assure that such coins did in fact contain the weight and fineness of metals they purported to.

Today, as we move further and further away from cash handling and make ever more use of electronic payments systems, it becomes easier and easier to appreciate that physical money - banknotes and coins - makes up only a very small proportion of the total money supply. While the amount changes over time and fluctuates seasonally, physical money is kept in the smallest amounts required to get the job done, minimizing cash handling and storage risks and costs.

Let’s imagine that we have a new economy, with as yet no physical money. Of course, we wouldn’t be left to stand around, scratching our heads and unable to interact with each other, simply because we had no money. We know that money is created in the process of facilitating debts and enabling trade. And we know that we can make the economy work with no physical money, albeit with some limitations. If all transactions could be carried out by instruction alone (instructing banks to debit this account and credit that one, by, for example, checks, payment cards or online banking/payment services), then we would have a cashless economy in which conceivably vast amounts of trade could be carried on. Entirely cashless economies might be a little unrealistic, even for us today, but appreciating how such a system works enables us to understanding more clearly the role physical money really plays. The essence of money is, of course, debt - an entirely non-physical phenomenon itself. But occasionally we need some physical 'stuff' on which to convey that non-physical information.

Let's now imagine that a physical money stock has been created and delivered/sold into the banking system where people like you and me can get access to it. If I have a positive bank balance of £1000, it doesn't mean that there's £1000 of physical money sat in the bank (or anywhere else) just for me. If that were the case, for all of us, 100% of the money supply would have to be represented by physical notes and coins - the vast majority of it just sat there, expensively doing nothing, for no practical reason at all. In reality, if I have £1000 in my account, then there will likely be less than about £50 of physical money in existence to support it; such is our limited need for physical money. So long as enough physical money exists that if I need to make a cash withdrawal I will be able to, then the system will work. And so long as an unusual or unexpected number of others don't want to do the same thing at the same time, then all will be fine.

Now, when I make a cash withdrawal, I'm simply swapping the numbers in my account for pieces of paper with the numbers written on them instead. (You could liken it to 'buying' physical money with non-physical money.) It's the same information - my legal title/claim - I just now hold it in a physical form, in my own hand. I can then pass that legal title on to whomever I wish to. Should I deposit the cash back in my bank, that process would simply reverse, swapping/'selling' pieces of paper with numbers on them for numbers in my own bank account. The pieces of paper, then, will go on to be used by the next customer who comes to the bank wishing to make a withdrawal so they can hold their numbers on pieces of paper too.

So we can see that physical money really only exists to support the much larger body of money that is just numbers. That's something we should bear in mind when evaluating discussions about money and historical accounts which emphasize the physical medium and overlook the potentially far greater body of legal monetary claims and debts which underlie it.

5. Banks as Credit Agents

For Households and Nation States

This is just a brief look at how the relationship between the financial sector and individuals or their governments should properly be. Inherently, it involves a consideration of the deep and far-reaching conflict between money as a tool for socioeconomic progress and money as a tool for often ruthless domination and extraction.

From almost any angle we might view it, money appears to be one of the most effective tools ever devised. From a 'politically neutral' perspective, merely as a tool for mediating exchange, money's power appears evident in almost every corner of the world today, and also at almost any point in history we might care to look.

But we know that money isn't polically neutral. In fact, one of the great testaments to money's irreplacable power lies in the fact that, despite being arguably the most corrupt medium to exist in our world and our history, it's hard for most of us to imagine life without it.

The hiearchical relations that dominate the world's economies today (and obviously trace far into our history) are built with money at their core. And it's hard to imagine them being able to build such structures without it. But we might equally believe, by contrast, that money can be just as effective in providng a foundation for democratic and human rights.

As already stressed, the debt/credit-based systems of money we have today are not only an inevitable development of money (because they are the most efficient way to mediate exchange, to occupy the space between giving and receiving), but they are also society's greatest opportunity for justice, for decency, for democracy, for human rights.

In the conventional view, banks 'lend' money from an already-existing stock; money that (rightly or wrongly), belongs to other people. Thus there is established a lender-borrower relationship and debtors are expected to pay interest, often in considerable sums. To this day, the idea that debts are facilitated by the lending and borrowing of already-existing money is the fundamental justification for interest taking. (Indeed there can surely be no other.)

Yet it's also clear that lender-borrower relations hold the potential to be among the most corrosive that can exist in society. There's no shortage of stories one can read about the many horrific injustices faced by debtors - not just in history, but continuing in the world today. These are tales of the wealthy extracting ruthlessly from those far worse off than themselves. But let's not fall into the trap of treating this subject with undue superficiality; the lender-borrower relation isn't something that pockmarks an otherwise honest, legitimate financial economy. The lender-borrower relation is of such profound effectiveness in creating and sustaining hierarchy that, for perhaps as long as we have written records, it's been employed systematically, to the very foundational architecture of economic society. Lender-borrower relations today continue to allow those architects to dominate and extract through both the private and public sectors of the world's economies.

Consider the tyrant who, merely by professing his own self-importance, lays claim to the major institutions of economic society, declaring to run them for his own private profit and returning a wage to those willing to serve him. Such behavior, being conspicuous, is likely to invite the anger and resentment of many of his now disenfranchised economic subjects. While it's true that some may continue to feel enfranchised, for having the opportunity to serve and earn a wage, many will recognize both the injustice of the tyrant's claims and the loss of their own rights and opportunity. The victims of colonial rule, of other forms of imperial domination and of slavery were contemptuous of those schemes and those behind them. Many dedicated themselves to rebellion and revolt. That isn't to say such methods didn't work, just that they're not the most stressless methods by which to conquer and extract from large numbers of people.

Now consider the tyrant who fashions an economy to be in debt to him. In all but the most gratuitous examples, what we expect to see are people quietly, obediently, handing up their own wealth and opportunity, along with national/public wealth, in order to satisfy the tyrant's supposed claims. Both tyrants deliver as much injustice, but they invite starkly contrasting reactions. The reason for that is surely that claims made about finances are disarming for people who are often ill-equipped to make sense of them, let alone enough sense to raise objections.

The extreme social inequalities and the great 'unpayable' volumes of debt that plague the world today are not new. Ancient rulers, understanding that such debts were so corrosive that they made the life of society unsustainable, periodically renounced them, initiating a kind of 'reset', albeit for a cycle of abuse that would begin all over again.

The kinds of highly exploitative financial relations that are the backdrop for these stories were of such notoriety to have been labelled and condemned by history as 'usury'. And it might even be one of the most important messages earlier civilizations sought to pass down.

The advantage we have today is that we know the foundation for these hierarchical relations is false. We know that the 'loanable funds' model of bank 'lending', the foundation for interest taking, is just not an accurate description of how we facilitate debts. We know that banks create the money we need, when we express demand for it. We know that none of us, nor our governments, are actually 'borrowing' anyone else's money. We know that every unit of currency created in the global economy should be created democratically. But we also know that, by the telling of one small story about 'lending' and 'borrowing', in fact all that money is created anti-democratically, hierarchically.

We can say, then, that we understand both the injustices committed by powerful financial actors, as well as how to stop them.

Household Mortgage Debt

Almost any discussion of real world economics could begin with the observation that the household is the foundation of economic life. The ability of people in every corner of the world to have a home and the opportunity to work, to pay for that home and the lives lived within it, is the very bedrock of any functional modern economy.

And if the truth is that we don't have to rely on banks 'lending' us other people's money when we seek out things like a mortgage, then it's clear that:

-

Anyone, everyone, can have unexploited, interest-free access to credit.

-

Banks participate in a relationship with their customers that should fit a horizontal rather than a hierarchical description.

Banks are the recorders or monetizers of our debts, they stand side-by-side with us in a relationship that debtors ultimately have with society. When money is created for our use, it is society that must accommodate that money and honor it whenever and wherever it is presented. Banks are facilitators of that process, agents through which these fundamental relations can take place.

I discussed in a previous article how, when the debts of ordinary people create money, for example to buy homes, that there is a real, outstanding debt which debtors have to pay; not because it was "someone else's money", but because the system can only work if the process is reversed again, if the debt/money is paid down. If that didn't happen, the system would be unfair and couldn't be sustained.

It's clearly first the debtor's responsibility to pay her/his debts. But it's also clear that in some circumstances debtors may not be able to do that. An important part of what the bank does, then, is to stand next in line, backing-up or underwriting the debtor in that responsibility. Where debts are secured, as they naturally are with household mortgage debts, the bank can seize and sell the securing property to settle the account. Only when the debt is un- or insufficiently secured are banks at risk of losing money. Banks, then, do face risks and costs in making their services available to us. That is what we should be paying them for. What we should not be doing is compensating them or anyone else for the "foregone use" or the "time value" of money. Banks can and should charge transparent, competitive fees for the services they provide; they have no need and no right to mislead customers in order to make supernormal profits at their expense.

Let's have a quick closer look at risk, in part because, when confronted with the fact that banks don't actually 'lend' other people's money, some will quickly switch to claiming that it is risk, rather than the 'foregone use' of money that is the basis for taking interest.

Well, in order to be exposed to risk, the bank must face an uninsured loss in the value of securing assets, such that their sale can no longer cover any outstanding sums against them (plus any costs of administration). Falling house prices, uninsured properties burning to the ground or being washed away in floods would indeed present such risks. But even at today's historically low interest rates (~5%), a homeowner will pay twice for their home over 30 years. If these payments were tied to risk, it would mean that, over each 30 year period, approx. 50% of the entire nominal value of mortgaged housing stock would be lost or destroyed without insurance, before any sums were paid against them. Such a belief or claim is obviously absurd.

So banks' interest taking isn't tied to risk. Banks take interest simply because they can, because bank customers don't understand the basic terms of the relations between them. The competitive market fees for originating, maintaining and settling a mortgage account would be a small fraction of their current level. If expressed as an interest rate, it would be surely a small fraction of 1%. Banks are taking tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, many years of life and a great deal of opportunity away from working families (and then often taking their home as well) simply because they have us believing we're "borrowing" other people's money.

From Households to Banks: The Gift that Keeps on Giving

In what is surely an inevitable travesty once interest on household mortgage debt has been accepted, the front-loaded mortgage allows banks to keep cashing in. Here, banks not only take huge sums of interest which they have no right to take, front-loading that interest simultaneously keeps the outstanding principal, on which interest is charged, as high as possible and delays its payment for as long as possible, pushing back as far as possible any claim a homeowner might have to her/his own home; something which will pay yet again when the bank gets to take the home itself, in the next routine collapse of the capitalist economy.

Over the 35 year period 1973 to 2007 (up to the crash), mortgage interest rates averaged around 9.3%,[1] almost exactly the rate required to make households pay three times for their homes; once for their home, twice as a gift to the already rich. And this will be repeated for each property, every time time a mortgage is channeled through it. Can we really understand the vast economic consequences of making the great majority pay so much extra for a home and sending it all to a few at the top?

And this says nothing of the much wider catastrophe of allowing such ruthless exploitation of people's need for a home. We are basically saying that people must pay three times for a home (or as much to rent), twice as a gift to the rich, or go without. Under these circumstances, it's impossible to believe that the neofeudal economy can provide housing security to many, let alone to all. Many millions of families globally face extreme economic disadvantage and the fact that they will never enjoy secure or adequate housing. All for the benefit of a small financial elite.

National Sovereign Debt

I've already covered how money created by governments for domestic spending cannot be conceived as a 'debt' in any conventional sense - that any obligation associated with this kind of public money creation is an obligation only to maintain the fairness and stability of the system. There is absolutely no legitimate requirement on nation states to 'collect back' all the money they issue. In fact they appear to have a quite counter obligation to provide a national currency base that is immune from such demands for repayment. This is true even though today money is created for governments as 'loans', thus as debts, in exactly the same way money is created for households and the wider private sector.

So there's a very important class of public debt - that associated with national currency creation - that should not be a debt at all.

But there are other areas worthy of brief consideration. For example, in the case that a government might have, or be perceived to have, debts to foreign entities denominated in any currency. Well, the reason we have money and banks exactly as they are is so that access to money - access to legitimat debt - can be facilitated on demand without the need for any actual lending or borrowing. Governments are not excluded from that. Banks create money through the process of recording into being our (or our governments') outstanding debts; no lending or borrowing is actually taking place and no interest should be asked for or given.

So, throughout finance, debts work by the endogenous creation of money as records of outstanding debt; it is not 'loans' and it is not 'borrowing'. To the extent these processes produce real debts, they should be interest free.

Finally, there's the idea that governments can provide savings instruments in the form of interest bearing bonds. Governments can sell bonds, not because they need to raise money, but to allow savers to make savings in a way that is safe and offers some protection against inflation (the decline in the value of our money over time).

The problem that exists here is the potential for wealthy investors to be in the market, not to protect the value of modest savings, but to enjoy a healthy, ongoing income at the taxpayer's expense. In a democracy, it's natural that people will ask "Who should be entitled to a rate of interest courtesy of the state and at taxpayers' expense?"

I've only touched very lightly on the main points of public debt here, but it's enough for good thought and action. Public debt is an important domain through which economic power is expressed over countries all over the world.

Help us fight to end that global injustice and replace it with basic economic literacy and real rights for all:

Basic economic literacy as an educational right.

Teach children where money comes from and why, how banks and debts basically work.

A democratic, debt and interest free national currency base.

Nations are currently required to "borrow" their currencies into existence from capitalist banks.

-

Interest free access to credit for households and all governments.

Banks create and destroy money as we go into and out of debt; interest beyond fees is unwarranted and unnecessary.

Footnotes

6. It's Just Not Scientific

The World's Most Powerfully Misused Words

The words 'lend' and 'borrow' already have their use and meaning in the world outside of finance. Say I have a bicycle and you would like to 'borrow' and make use of it for a period before returning it to me, I could 'lend' that bicycle to you and the interaction between us really would be an example of what our language ordinarily conveys by the words 'lending' and 'borrowing'.

The words 'lend' and 'borrow' already have their use and meaning in the world outside of finance. Say I have a bicycle and you would like to 'borrow' and make use of it for a period before returning it to me, I could 'lend' that bicycle to you and the interaction between us really would be an example of what our language ordinarily conveys by the words 'lending' and 'borrowing'.

And if we invoke the legal construct of the 'reasonable person', I'm sure that if you approached a 'reasonable person' in the street and asked them what they thought those words mean, you'd get the very same definition I offered there.

But banks of course don't do that. Banks record money into and out of existence in the process of facilitating our debts. In the case of households, we understand that these really are real debts, but we understand they are not the result of any "lending" or "borrowing" in the commonly, reasonably accepted understanding of what those words mean. Money is endogenous and creditary; money is debt and it comes into and out of existence when we go into and out of debt.

In my experience, it's not too uncommon to find other economists or finance professionals who understand that money works this way (something they might call "multiplying money" or "expanding banks' balance sheets"). What is much harder to find are those among them who recognize that there's something fundamentally wrong in couching these processes in the extraordinarily misleading language of 'lending' and 'borrowing', or indeed show the right concern for its consequences - the establishment of very cruel and unnecessary, hierarchical lender-borrower relationships which crush and loot the economies and people of the entire world.

Recording money into and out of being, as records of outstanding indebtedness, is, clearly, an existentially different phenomenon to that of the borrowing and returning of already-existing money that is the rightful property of the lender. This is a basic fact any schoolchild could readily understand. Yet we find our highest academic, financial and political communities and authorities perpetuating this language and then raising far too few concerns about the damages being done as a consequence.

This is a clear case of the abuse of, or at best the unscientific treatment of, language. I'm sure there are many professionals who use these terms unconsciously or uncritically, who, for a lack of a better understanding themselves, believe or have assumed that banks really do 'lend' 'borrowers' other people's money. But even so, that isn't what we expect from professionals. From the professional community we expect honesty and accuracy. And as much as there may be some whose use of this language could be considered uncritical, there are clearly many others who know this is an inappropriate and misleading language, yet use it anyway.

The economics community is suffering a crisis of reputation, as I'm sure it does permanently - and certainly every time the world descends into even more calamity and it's revealed that those at the top have simply been plundering all along. With the rise of communications technology, more people every day are coming to understand that this type of economics is systematically unjust, that society is lost to corruption and about as far from the ideals of decency and democracy as economies ever have been.

If you know, as children can and should know, that money is created for us when we need it, when we go into debt, would you still be happy to hand up large sums of your hard-earned income - many thousands of hours of your working life - in interest payments to people who are not only already rich, but simply did not earn and do not deserve that money? Would you be happy to see the great majority of the working population around you do the same? At 9.3% (the 35 year average mortgage rate to the 2007/8 crash), a working families will pay almost 3 times for their home; twice as a mere gift to the already rich. We don't need to look much further to see how it is they acquired that wealth in the first place, or how such small numbers of people come to own everything of value in society - and now just about everything of value on Earth.

If you knew that very much of the world's "national debts" were also the result of simple money creation, not the actual lending and borrowing of anyone's money, would you continue to accept the endless mainstream chatter about deficits, over-spending and the cost of public services and public debt? Would you accept "austerity", the loss of public rights and public assets in the name of "paying up" and "living within our means"? Would you accept the unconscionable drain private international banks inflict on many of the poorest nations in the world? Would you still believe the capitalist system is one of justice and fairness, where wealth is "earned", where we reward 'enterprise', 'endeavor' and 'merit'? Or would you suspect that this is all just wallpaper for great frauds and corruption; perhaps the greatest examples of such in all of history? I don't imagine for a minute that you'd fail to have serious concerns about what is going on; I think you'd look very differently at how property, income and opportunity has been allocated under capitalism and I think you'd wonder exactly what alternatives we are being deprived.

So maybe we can go from understanding it's all set up by and for a corrupt few to actually doing something about it. Basic economic literacy is the foundation for a better economic future, for genuine democracies and for economics founded on the real rights of all. Let's do something now, if only for the sake of the world's poorest (enormous numbers of whom lose their fight against global capitalism every day). Let's make sure we're still around to see life and opportunity returned to those from whom they are currently being stolen. And that's pretty much every last person on Earth, including economists. What might the world look like then?

7. Capitalism

The Basic Economics

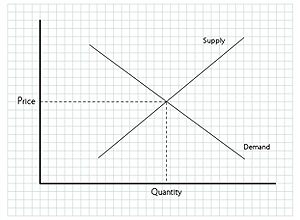

- Fig 1 -

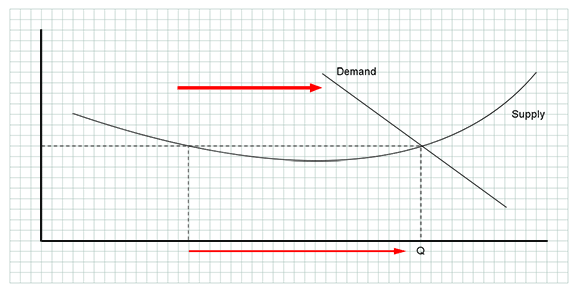

In our earliest studies of economics, we're introduced to the idea of supply and demand (click the pictures to enlarge them). And despite the many complications this simple analysis can gloss over, I think it can be an important thinking tool nonetheless.

In his book Debunking Economics, economist Steve Keen, drawing on the work of Italian economist Piero Sraffa, points to the likelihood that the supply curve is not, in fact, upward sloping. At least, not in the estimation of business leaders or by empirical measurement of the world around us at this time.[1] For Keen, the supply curve (the upward sloping line) is more likely to be horizontal, or even downward sloping (see Fig 2). And what that shows is that our ability to produce and to supply is not being constrained by the conditions of supply, but rather by the conditions of demand. We could potentially produce more and at lower unit costs than we do at the present time.

Another way of saying that is we're being held back. Rather than nurturing us to do the best we can with what we have, the economy subjects us instead to some kind of malorganisation or influence that either simply wastes our capacity or is perhaps redirecting it. And that's a conclusion that fits with our wider view that capitalism unfairly distributes market power upwards, towards an undemocratic few at the expense and often the exclusion of everyone else. It would also suggest that fixing it isn't a matter of improving supply side conditions like technology, but rather demand side conditions which concern the economic/market power of the ordinary majority. (This would push the demand curve - the downward sloping line - outwards to the right.)

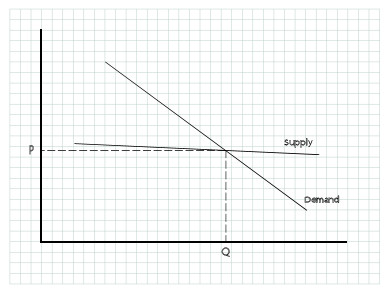

- Fig 2 -

And that would seem to provide support for the idea that the problems of capitalist economics are systemic and internal, rather than imposed by the natural world or the present state of human capability. If so, then what we're dealing with are distortionary pressures which render the majority unable to demand that which we are able to produce. And it's a truly basic economic fundamental that if it cannot be demanded, it will not be produced:

Although aimed at highlighting the conditions of employment, Hanauer's comment conveys very clearly the primacy of demand in driving the productive process i.e. the economy.

Capitalism, of course, is hierarchical and distortionary by design. What else could an interest rate attached to all circulating currency possibly produce? Looking still at the demand side of our supply-demand graph, disenfranchising the majority, leaving many economically deprived or even excluded can be shown as the demand curve being pushed backwards towards the left. Output is lowered, prices are higher than they might otherwise be and, because market opportunity is being transferred from poor to rich, productive output (Q) is directed away from what people do want (rendering that demand latent) and towards the wants or demands of an unjustly empowered few.

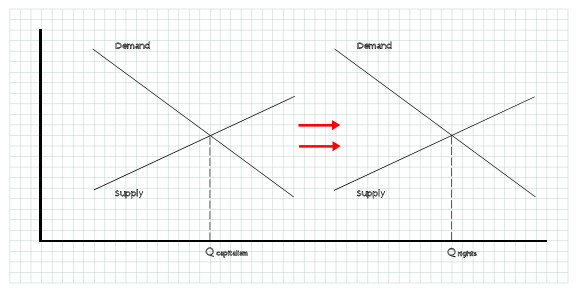

It seems reasonable to postulate, then, that Keen's observations and orthodox neoclassical economic theory might find some eventual resolution in the following graph. Here, diminishing marginal productivity and rising marginal costs do set in eventually (the supply curve sloping up), but at a level and type of output that meets the needs and interests of many more people than can be achieved under capitalism.

- Fig 3 -

Fig 3 shows the potential influence of democratic and human rights enfranchising many more people. Economic power now emerges more from the bottom up, the social hierarchy flattens and the demand curve moves outwards to the right. Production now reflects the needs and interests of the many, not the few. Note that the needs of 7+ billion people must be produced within Q. Improved democratic and human rights, then, may allow people all over the world to be brought back into the embrace of human creative ingenuity.

And I hope you agree that sounds a lot better than the injustice, conflict and hostility that exists all around us today.

I gave my reasons why we should prioritize demand in our analysis. But supply and demand are inherently entwined and there is a supply side argument that some might make to defend capitalism and the status quo. If on one side we say that capitalism is unfair, that it is exclusionary and distortionary, on the other, one might argue that class hierarchy, domination and extraction are drivers of productivity. Here, it is the capitalist whip that makes us all productive and keeps us from falling into a life of "indolence". It's a "slavery is productive" kind of argument, but it's the sort of argument that stirs unmentioned under the surface of many orthodox commentaries. Could real democratic and human rights bring about a catastrophic collapse in things like labour participation or discipline?

Some counters to such worries argue that withdrawing cultural and legal support for slavery didn't bring about a catastrophic collapse in economic productivity, even though many at the time proclaimed with the greatest alarm that it would. But of course, the wider conditions of economic domination and the subjugaton of labour were left intact. Society was and remains steeply hierarchical. And it's staggering to contemplate, but many believe the number of people subject to economic conditions deserving to be called 'slavery' are today perhaps as numerous as they may ever have been. Capitalism remains history's greatest and ongoing humanitarian emergency.

We do expect democratic and human rights to have supply side effects, we do expect them to change the lives and conditions of the majority working and poor. We want people to have greater rights, greater freedoms and the ability to derive greater benefit from their work. We want the economy to change considerably. But would people still "slave away" at their jobs, or at other jobs, in a post-capitalist economy? Do people need to be subordinated in order to remain productive? What kinds of structures would freer people maintain and what structures might go away? It's perhaps an impossible argument to evaluate: On one side the idea that capitalism might be "doing the right thing" by dominating and dictating, by opposing democratic and human rights globally, by whipping the working/second class majority into action. It's upsetting to think the rich ruling over and extracting from the poor is what's "best for everyone", that this hierarchy and often soulless drudgery is the best we can hope for.

On the other is the promise of greater rights and inclusion for all, but a world largely unknown and thus subject to much greater speculation. We can observe from all around the world that placing emphasis on things like literacy and the rights/uplift of the common majority, of often deeply deprived/disenfranchised sections of society, has an uplifting effect on society as a whole. Indeed, that ideas like democracy or civility themselves cannot exist in their absence. I don't believe any society has traversed the span from oligarchic/monarchic feudalism to the modern-day pretense of democracy without doing exactly that. And surely it's axiomatic that real democracy means 'fair rights for all', that democracy, thus civility, does not and cannot exist until such a condition has been (at least approximately) met.

But that only seems to offer a half answer to the question of whether freer people will still work; will they still produce the things that they and everyone else want to consume? Well, there's no reason to believe that greater human and democratic rights would collapse what we know of the productive structures of economic life. Their nature and purpose is to collapse the parasitic. People will still need money, they'll still organise, in firms and within the public sector, thus they will still produce. It's just that the economy as a whole will produce different things and more fairly distribute the benefits of that production.

If people who today are economically excluded are tomorrow included, they will bring their ingenuity, their creativity and their enterprise into the productive arena. People who are deprived their rights, dispossessed and overlooked can't participate in life as they would like to - *as they would like to*. Such people simply never receive the inputs and opportunities they need to develop their potential. Economically enfranchised people are much more likely to, indeed, may be the only ones who can.

So, supply side factors that affect productivity positively in a post-capitalist, democratic society, might balance or even outweigh productivity losses brought about by undermining the harsh, 'disciplining' conditions of capitalism, economic subjugation and exclusion. And that could mean that, even if Keen's assertion turned out to be wrong, even if the conditions of supply today are indeed more constrained than Keen believes them to be and supply curves do slope upwards, the inclusion of so many disenfranchised people through democratic and human rights could ensure that even upward sloping supply curves can be pulled outwards to the right by outward shifting demand curves. These are the inventions, the innovations, the enterprise that economically included people can bring, that economically disenfranchised/excluded people cannot.

- Fig 4 -

I'm convinced that the economic subjection and injustice of capitalism is not only offensive to human dignity, but also harmful to the supply and demand conditions of all economic life. I'm convinced that we're being deprived of a much richer, deeper, broader economy for nothing more than the power and prestige of a few. I do not believe they are saddened by the human cost of that privilege! I'm convinced that democratic and human rights have the power to open the way to an entirely better economic reality for us all, even though I'd happily hear arguments to the contrary from any willing to try.

Until then, with urgency, let us promote:

-

Basic economic literacy as a child's educational right.

Debt and interest free national public currency creation.

-

Interest free access to money for all households and all governments.

Footnotes

1. See: Debunking Economics, chapter 5, 'The Price of Everything and the Value of Nothing'. ↩

8. Accounting for Money Creation - 1

Introducing Governments and Banks

We've seen how money, banking and debt, in truth, basically work and we've considered a few conceptual ideas to strengthen our understanding of what is going on, what is going wrong and how we might fix it.

Let's now return to our original example and expand on the basic financial/credit system we built in section 1. We'll look more closely at how the creation, transfer and settlement of money is or can be accounted for. And we'll build the system up to capture more of the real world, including adding a government and a plurality of banks.

This is where we left our community:

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | 0 | 0 |

| Jo | 2000 | 0 |

| Cassie | 0 | 0 |

| Lauren | 0 | 1000 |

| Sean | 0 | 1000 |

- Table 1 -

Introducing Governments

Let's now introduce a government (which we'll assume is Mark, Jo, Cassie, Lauren and Sean themselves). We want to see government finances and government money creation in action, so we'll have the government simply credit each community member with 1000 units, either for no reason at all other than that they might have some money, or in payment for their contributed labor - perhaps for building some roads.

| Name | Credits | Debts |

|---|---|---|

| Mark | 1000 | 0 |

| Jo | 3000 | 0 |

| Cassie | 1000 | 0 |

| Lauren | 1000 | 1000 |

| Sean | 1000 | 1000 |

| Government | 0 | 5000 |

- Table 2 -

This action created a body of money (5000 units) which now allows community members to make savings without an accompanying real debt. You can see that this money creation is recorded as a debt. And for the purpose of continuing with banking conventions, we'll continue to record it as such throughout these examples. But here you can see why it is that this money is called debt and why it is, falsely, assocaited with 'lending and borrowing'. It is solely by these conventions that this language is used; it really does not mean that any of the community members, having earned or been given this money, should "owe" it back again. I discuss here how, even with debt-based currencies, public money creation is an obvious special case; if it can be described as a debt, it is a "debt we owe ourselves" and therefore not a debt at all. The community can theoretically create as much money as they like, their only concerns are to maintain 1. the fairness and 2. stability of the system. Overlooking such details for the time being, it's quite clear that the community just created some money, it did so democratically and doesn't "owe" anyone anything for doing it.

Some will surely object to governments being able to create money. However, someone has to. And every unit of currency created should be created fairly, democratically. In our example of government money creation, the government created a base money supply and allowed community members to make savings of an extra 1000 each, without having to burden anyone with real debts and thus demands for repayment. It also aided them in organizing themselves to achieve something in the first place, like building roads. Finally, just like anybody else honoring a debt, should it be necessary to do so, governments can always eliminate money by taking it out of the economy through revenues and out of existence. Here, the government's revenues are conceptually no different to Mark charging for his services as a roof repairer.

We're still quite early in building our system, but we can already contrast it with capitalistic alternatives. In the capitalist economy, because all money, whether issued through the private or public sector, is issued as 'loans', we can see very clear structures of extraction and control. In the capitalist economy, money circulates:

-

As the property of a capitalist elite.

-

At their discretion. (Put it in, take it away 'business cycles'.)

-

As an interest bearing debt to them. (Tribute economy.)

Those hierarchical or 'class' relations do not exist in our sample economy.

Introducing Banks

Our little community system has given us a good start in understanding how money, banks and debts really work. Let's now make it a little more realistic by introducing banking as a formal practice.

In the following examples we'll use a conventional accounting structure. But the reader may observe that the language and conventions are very much those of exogenous, rather than endogenous concepts of money. It remains entirely possible that better conventions could exist to account for the creation, circulation and eventual settlement of money.

We're keeping it nice and simple, so just one bank to cater to the whole community and still no physical cash stock; all money is no more than the non-physical numerical records you see in the tables and all payments are performed by instruction i.e. by credit/debit cards, checks, telephone, internet etc. We'll take the numbers from above and put them into a new table:

| Banks | Individuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 0 | 1000 | Mark | 1000 | 0 |

| 0 | 3000 | Jo | 3000 | 0 |

| 0 | 1000 | Cassie | 1000 | 0 |

| 1000 | 1000 | Lauren | 1000 | 1000 |

| 1000 | 1000 | Sean | 1000 | 1000 |

| 5000 | 0 | Government | 0 | 5000 |

- Table 3 -

The language of 'credits' and 'debts' has been changed to 'assets' and 'liabilities'. By showing the bank's accounts alongside those of its customers, we can see how any adjustments made to an individual's account are reflected in the bank's own accounts. The bank's accounts can be seen to mirror those of its customers; a customer's debt is an asset for the bank and the bank's debt is an asset for the customer.

When somebody goes into debt, the process of money creation is captured by the bank creating a checkable deposit (spendable money) for that person to draw on, recording it as an 'asset' for the debtor and balancing it by their 'liability' to repay it. Commensurately, banks take a mirror position: they record that newly created money as a liability for themselves (as if they're 'holding' this money in a physical sense and have the liability to give it back) and record the credit agreement as an asset - a document which allows the bank to collect repayment + interest, as well as access the legal system if a debtor falls delinquent.

So, whenever the bank creates new money, we'll see all 4 columns along the row adjusted by the same number. This is why money creation by banks is often called a balance sheet expansion. Let's imagine that Cassie goes to the bank for credit of 2000; the bank's books would be adjusted to add 2000 to each column accordingly:

| Banks | Individuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 0 | 1000 | 1000 | 0 | |

|

|

Cassie |  |

|

| 2000 | 3000 | 3000 | 2000 | |

- Table 4 -

2000 new currency units were made available to Cassie, recorded both as an asset and liability of her own, but now also mirrored for the bank: Cassie's asset is the bank's liability and her liability is the bank's asset.

The whole table now looks like:

| Banks | Individuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 0 | 1000 | Mark | 1000 | 0 |

| 0 | 3000 | Jo | 3000 | 0 |

| 2000 | 3000 | Cassie | 3000 | 2000 |

| 1000 | 1000 | Lauren | 1000 | 1000 |

| 1000 | 1000 | Sean | 1000 | 1000 |

| 5000 | 0 | Government | 0 | 5000 |

- Table 5 -

If you've seen the first of our little pieces 'How Money Really Works', you'll know that we can perform any operation required on these numbers, any transactions, as well as facilitating any reasonable level of debt for any member, without any need to invoke language like "lending" or "borrowing". No actual lending or borrowing is necessary to facilitate this community's debts or, as you've seen, any pulic money creation. All processes consist either of creating numbers, transferring those numbers by instruction (by debiting one account and crediting another), or eliminating numbers when debts are paid down (positive numbers paid into negative balance accounts cancels money out of existence). So, even though we've introduced a government and a bank, we've retained what we started with: an honest, inclusive and interest free financial system which can accommodate all community members and a government without anyone having to "borrow" anything from anyone.

We've showed that banks can serve a community, that introducing them into our model didn't have to condemn us all to class hierarchy and systemic usury. In the next section we'll develop the model to introduce a plurality of banks.

9. Accounting for Money Creation - 2

Introducing a Plurality of Banks

In the previous section, I built on our earliest look at how money really works and established that we could continue to develop that example economy, to include a government and formal banking, and retain a form that was democratically legitimate and fair, that did not subjugate the community to class hierarchical relations and systemic usury.

And although I think we proved right at the beginning that our financial systems can work to support the democratic and human rights of people everywhere, we can continue build our example economy, adding more realism, this time by introducing a plurality of banks.

Introducing A Plurality of Banks

Picking up from where we left off, let's now introduce a second bank. I'll just cut the table through the middle and move Lauren, Sean and the Government to Bank 2. I've also included a row for totals, so we can see the total assets and liabilities for the bank and its customers. Despite the misnomer, we retain the word "Loans".

| Bank 1 | Individuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 0 | 1000 | Mark | 1000 | 0 |

| 0 | 3000 | Jo | 3000 | 0 |

| 2000 | 3000 | Cassie | 3000 | 2000 |

| 2000 | 7000 | 7000 | 2000 | |

| Bank 2 | Individuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 1000 | 1000 | Lauren | 1000 | 1000 |

| 1000 | 1000 | Sean | 1000 | 1000 |

| 5000 | 0 | Government | 0 | 5000 |

| 7000 | 2000 | 2000 | 7000 | |

- Table 1 -

We can see that there are still 9000 currency units in circulation (the total of customer deposits/bank liabilities). What we want to explore is how moving money between customer accounts at these banks works out; we just want to ensure that nothing unpleasant materialises that would threaten the system and reintroduce notions of lending and borrowing. Because of our arbitary slicing of the table into two separate banks, we can see that Bank 1 has assets far below its liabilities (which by convention would mean it's failing) and Bank 2 has assets far above its liabilities, meaning it's doing excessively well.

Because customer deposits here are liabilities, transferring them between banks would change their asset-liability ratios. Banks taking deposits would take on greater liabilities and thereby worsen their financial position; those transferring deposits out would see theirs improve. To tackle this problem, we can introduce another layer of banking - a bank for banks. Here, this will be the central bank (CB). And this allows banks, who hold accounts with the CB, to move assets between themselves. This means that when a customer deposit (bank liability) is moved from one bank to another, an asset can move along with it, neutralizing the effect of moving that money from one bank to another. Because the central bank is also the government's bank, we'll put the government's account there too. To give us some assets to move, I'll have the central bank create 10,000 for each bank:

| Central Bank | CB Customers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 5000 | 0 | Government | 0 | 5000 |

| ▴10,000 | ▴10,000 | Bank 1 | ▴10,000 | ▴10,000 |

| ▴10,000 | ▴10,000 | Bank 2 | ▴10,000 | ▴10,000 |

| 25,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | 25,000 | |

| Bank 1 | Individuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 0 | 1000 | Mark | 1000 | 0 |

| 0 | 3000 | Jo | 3000 | 0 |

| 2000 | 3000 | Cassie | 3000 | 2000 |

| CB Cash | CB Debt | |||

| 10,000 | 10,000 | |||

| 12,000 | 17,000 | 7000 | 2000 | |

| Bank 2 | Individuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 1000 | 1000 | Lauren | 1000 | 1000 |

| 1000 | 1000 | Sean | 1000 | 1000 |

| CB Cash | CB Debt | |||

| 10,000 | 10,000 | |||

| 12,000 | 12,000 | 2000 | 2000 | |

- Table 2 -

We can now move customer deposits between banks 1 and 2, showing both liabilities as well as assets moving. We'll have Cassie spend her 2000 'loan' equally between Lauren and Sean. Notice that we begin (above) with Bank 1's net assets at -5000 and Bank 2's net assets at 0. Previously, if we'd moved customer deposits from one bank to another, that would have raised the sending bank's net assets and lowered the receiving bank's. Now, when Cassie's bank (Bank 1) transfers her payments to Lauren and Sean at Bank 2, it makes a net 2000 transfer of assets from its account at the CB to Bank 2's:

| Central Bank | Banks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Assets | Liabilities | |

| Loans | Deposits | Deposits | Loans | |

| 5000 | 0 | Government | 0 | 5000 |

| 10,000 | ▾8,000 | Bank 1 | ▾8,000 | 10,000 |

| 10,000 | ▴12,000 | Bank 2 | ▴12,000 | 10,000 |

| 25,000 | 20,000 | 20,000 | 25,000 | |