|

7. Capitalism |

The Basic Economics

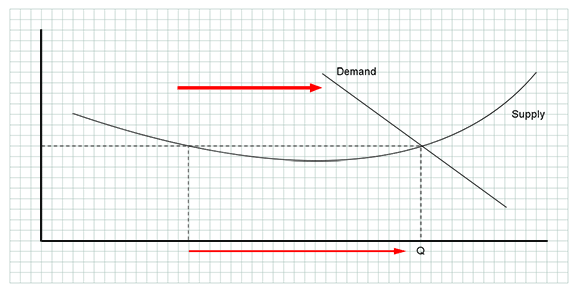

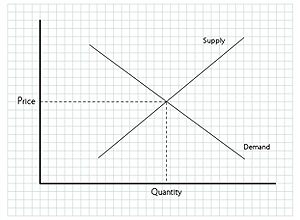

- Fig 1 -

In our earliest studies of economics, we're introduced to the idea of supply and demand (click the pictures to enlarge them). And despite the many complications this simple analysis can gloss over, I think it can be an important thinking tool nonetheless.

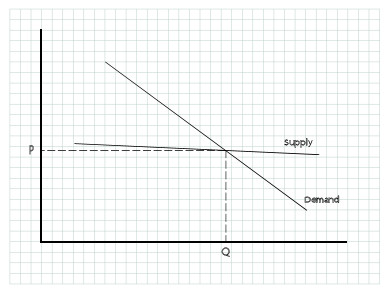

In his book Debunking Economics, economist Steve Keen, drawing on the work of Italian economist Piero Sraffa, points to the likelihood that the supply curve is not, in fact, upward sloping. At least, not in the estimation of business leaders or by empirical measurement of the world around us at this time.[1] For Keen, the supply curve (the upward sloping line) is more likely to be horizontal, or even downward sloping (see Fig 2). And what that shows is that our ability to produce and to supply is not being constrained by the conditions of supply, but rather by the conditions of demand. We could potentially produce more and at lower unit costs than we do at the present time.

Another way of saying that is we're being held back. Rather than nurturing us to do the best we can with what we have, the economy subjects us instead to some kind of malorganisation or influence that either simply wastes our capacity or is perhaps redirecting it. And that's a conclusion that fits with our wider view that capitalism unfairly distributes market power upwards, towards an undemocratic few at the expense and often the exclusion of everyone else. It would also suggest that fixing it isn't a matter of improving supply side conditions like technology, but rather demand side conditions which concern the economic/market power of the ordinary majority. (This would push the demand curve - the downward sloping line - outwards to the right.)

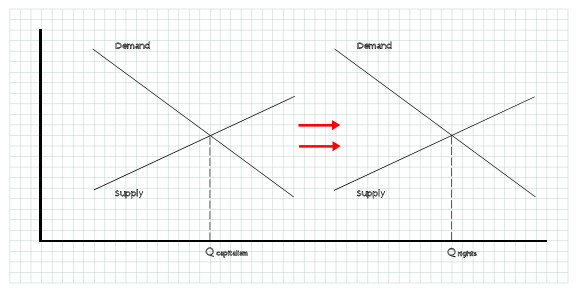

- Fig 2 -

And that would seem to provide support for the idea that the problems of capitalist economics are systemic and internal, rather than imposed by the natural world or the present state of human capability. If so, then what we're dealing with are distortionary pressures which render the majority unable to demand that which we are able to produce. And it's a truly basic economic fundamental that if it cannot be demanded, it will not be produced:

Although aimed at highlighting the conditions of employment, Hanauer's comment conveys very clearly the primacy of demand in driving the productive process i.e. the economy.

Capitalism, of course, is hierarchical and distortionary by design. What else could an interest rate attached to all circulating currency possibly produce? Looking still at the demand side of our supply-demand graph, disenfranchising the majority, leaving many economically deprived or even excluded can be shown as the demand curve being pushed backwards towards the left. Output is lowered, prices are higher than they might otherwise be and, because market opportunity is being transferred from poor to rich, productive output (Q) is directed away from what people do want (rendering that demand latent) and towards the wants or demands of an unjustly empowered few.

It seems reasonable to postulate, then, that Keen's observations and orthodox neoclassical economic theory might find some eventual resolution in the following graph. Here, diminishing marginal productivity and rising marginal costs do set in eventually (the supply curve sloping up), but at a level and type of output that meets the needs and interests of many more people than can be achieved under capitalism.

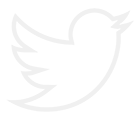

- Fig 3 -

Fig 3 shows the potential influence of democratic and human rights enfranchising many more people. Economic power now emerges more from the bottom up, the social hierarchy flattens and the demand curve moves outwards to the right. Production now reflects the needs and interests of the many, not the few. Note that the needs of 7+ billion people must be produced within Q. Improved democratic and human rights, then, may allow people all over the world to be brought back into the embrace of human creative ingenuity.

And I hope you agree that sounds a lot better than the injustice, conflict and hostility that exists all around us today.

I gave my reasons why we should prioritize demand in our analysis. But supply and demand are inherently entwined and there is a supply side argument that some might make to defend capitalism and the status quo. If on one side we say that capitalism is unfair, that it is exclusionary and distortionary, on the other, one might argue that class hierarchy, domination and extraction are drivers of productivity. Here, it is the capitalist whip that makes us all productive and keeps us from falling into a life of "indolence". It's a "slavery is productive" kind of argument, but it's the sort of argument that stirs unmentioned under the surface of many orthodox commentaries. Could real democratic and human rights bring about a catastrophic collapse in things like labour participation or discipline?

Some counters to such worries argue that withdrawing cultural and legal support for slavery didn't bring about a catastrophic collapse in economic productivity, even though many at the time proclaimed with the greatest alarm that it would. But of course, the wider conditions of economic domination and the subjugaton of labour were left intact. Society was and remains steeply hierarchical. And it's staggering to contemplate, but many believe the number of people subject to economic conditions deserving to be called 'slavery' are today perhaps as numerous as they may ever have been. Capitalism remains history's greatest and ongoing humanitarian emergency.

We do expect democratic and human rights to have supply side effects, we do expect them to change the lives and conditions of the majority working and poor. We want people to have greater rights, greater freedoms and the ability to derive greater benefit from their work. We want the economy to change considerably. But would people still "slave away" at their jobs, or at other jobs, in a post-capitalist economy? Do people need to be subordinated in order to remain productive? What kinds of structures would freer people maintain and what structures might go away? It's perhaps an impossible argument to evaluate: On one side the idea that capitalism might be "doing the right thing" by dominating and dictating, by opposing democratic and human rights globally, by whipping the working/second class majority into action. It's upsetting to think the rich ruling over and extracting from the poor is what's "best for everyone", that this hierarchy and often soulless drudgery is the best we can hope for.

On the other is the promise of greater rights and inclusion for all, but a world largely unknown and thus subject to much greater speculation. We can observe from all around the world that placing emphasis on things like literacy and the rights/uplift of the common majority, of often deeply deprived/disenfranchised sections of society, has an uplifting effect on society as a whole. Indeed, that ideas like democracy or civility themselves cannot exist in their absence. I don't believe any society has traversed the span from oligarchic/monarchic feudalism to the modern-day pretense of democracy without doing exactly that. And surely it's axiomatic that real democracy means 'fair rights for all', that democracy, thus civility, does not and cannot exist until such a condition has been (at least approximately) met.

But that only seems to offer a half answer to the question of whether freer people will still work; will they still produce the things that they and everyone else want to consume? Well, there's no reason to believe that greater human and democratic rights would collapse what we know of the productive structures of economic life. Their nature and purpose is to collapse the parasitic. People will still need money, they'll still organise, in firms and within the public sector, thus they will still produce. It's just that the economy as a whole will produce different things and more fairly distribute the benefits of that production.

If people who today are economically excluded are tomorrow included, they will bring their ingenuity, their creativity and their enterprise into the productive arena. People who are deprived their rights, dispossessed and overlooked can't participate in life as they would like to - *as they would like to*. Such people simply never receive the inputs and opportunities they need to develop their potential. Economically enfranchised people are much more likely to, indeed, may be the only ones who can.

So, supply side factors that affect productivity positively in a post-capitalist, democratic society, might balance or even outweigh productivity losses brought about by undermining the harsh, 'disciplining' conditions of capitalism, economic subjugation and exclusion. And that could mean that, even if Keen's assertion turned out to be wrong, even if the conditions of supply today are indeed more constrained than Keen believes them to be and supply curves do slope upwards, the inclusion of so many disenfranchised people through democratic and human rights could ensure that even upward sloping supply curves can be pulled outwards to the right by outward shifting demand curves. These are the inventions, the innovations, the enterprise that economically included people can bring, that economically disenfranchised/excluded people cannot.

- Fig 4 -

I'm convinced that the economic subjection and injustice of capitalism is not only offensive to human dignity, but also harmful to the supply and demand conditions of all economic life. I'm convinced that we're being deprived of a much richer, deeper, broader economy for nothing more than the power and prestige of a few. I do not believe they are saddened by the human cost of that privilege! I'm convinced that democratic and human rights have the power to open the way to an entirely better economic reality for us all, even though I'd happily hear arguments to the contrary from any willing to try.

Until then, with urgency, let us promote:

-

Basic economic literacy as a child's educational right.

Debt and interest free national public currency creation.

-

Interest free access to money for all households and all governments.

Footnotes

1. See: Debunking Economics, chapter 5, 'The Price of Everything and the Value of Nothing'. ↩

|

||

previous |

return |

next |

Anyone who's ever run a business knows that hiring more people is a course of last resort for capitalists. It's what we do if, and only if, rising consumer demand requires it.

Anyone who's ever run a business knows that hiring more people is a course of last resort for capitalists. It's what we do if, and only if, rising consumer demand requires it.